Who was Frank H. Netter, MD?

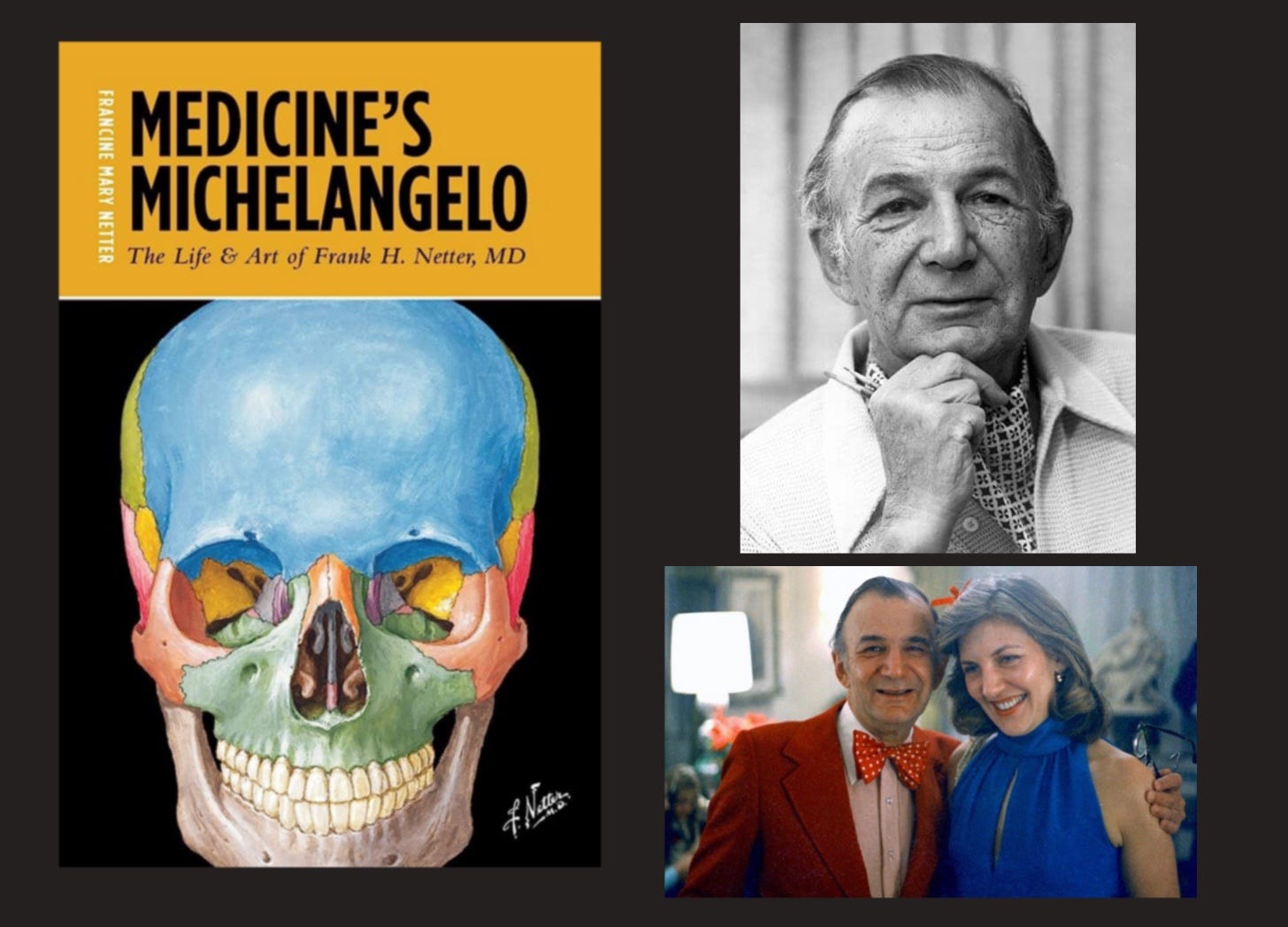

Book review of Medicine's Michelangelo: The Life and Art of Frank H. Netter, MD by Francine Mary Netter

About 20 years ago, I finished my medical training and moved from Boston to Charlotte. I had packed all my precious medical textbooks into a sturdy box. Unfortunately, the movers misplaced this box during the move. This led me to a dilemma: do I need to repurchase all my old books? I had passed all my exams and taken all my classes. I didn’t need any of these books anymore. But I was a little sad. I had spent countless hours with these books. Was I ready to let them all go? I decided not to repurchase my precious books. But I just couldn’t let go of one. I had to buy it again. Not because I needed to dissect any more cadavers for Gross Anatomy lab or learn how to perform surgery. But because the book had such a deep and special meaning to me. For my generation and probably many generations before and after, this book was a huge influence. I would guess that most medical professionals have studied and probably owned this book at some point in their lives.

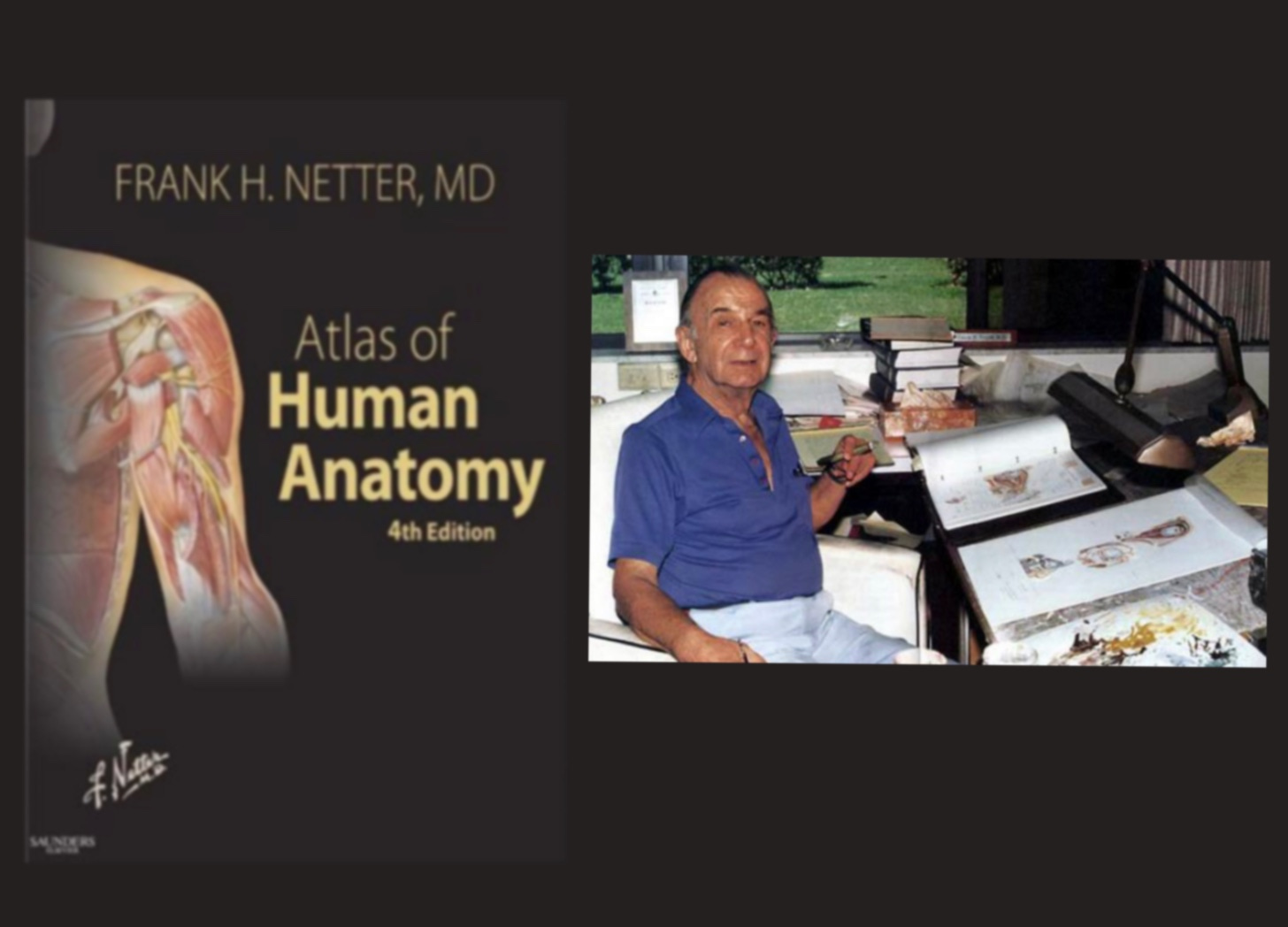

I realized that I didn’t know much about Dr. Frank Netter. Of course, I remembered that picture in the back of the Atlas of him in his polo shirt, smoking his cigar, while drawing in his studio. So I was thrilled when I came across this book (first published in 2013). It’s written by his daughter, Francine Mary Netter. She writes about the time when he received an honorary degree from Georgetown University, “when others spoke, students politely clapped. However, when he spoke, students cheered and stood up. The students never met him or heard him lecture, but they felt that he was their teacher. Their mentor. Their greatest teacher.”

I thoroughly enjoyed this book. I would highly recommend it to those of you who are interested in medicine and medical illustration. In case you do not have time to read the whole book, here’s a quick summary of the life of the amazing Dr. Frank Netter. I’ve mainly added parts that resonated most with me. Many of the following pictures were taken from this text.

Book Summary

Early Life (1906-1990)

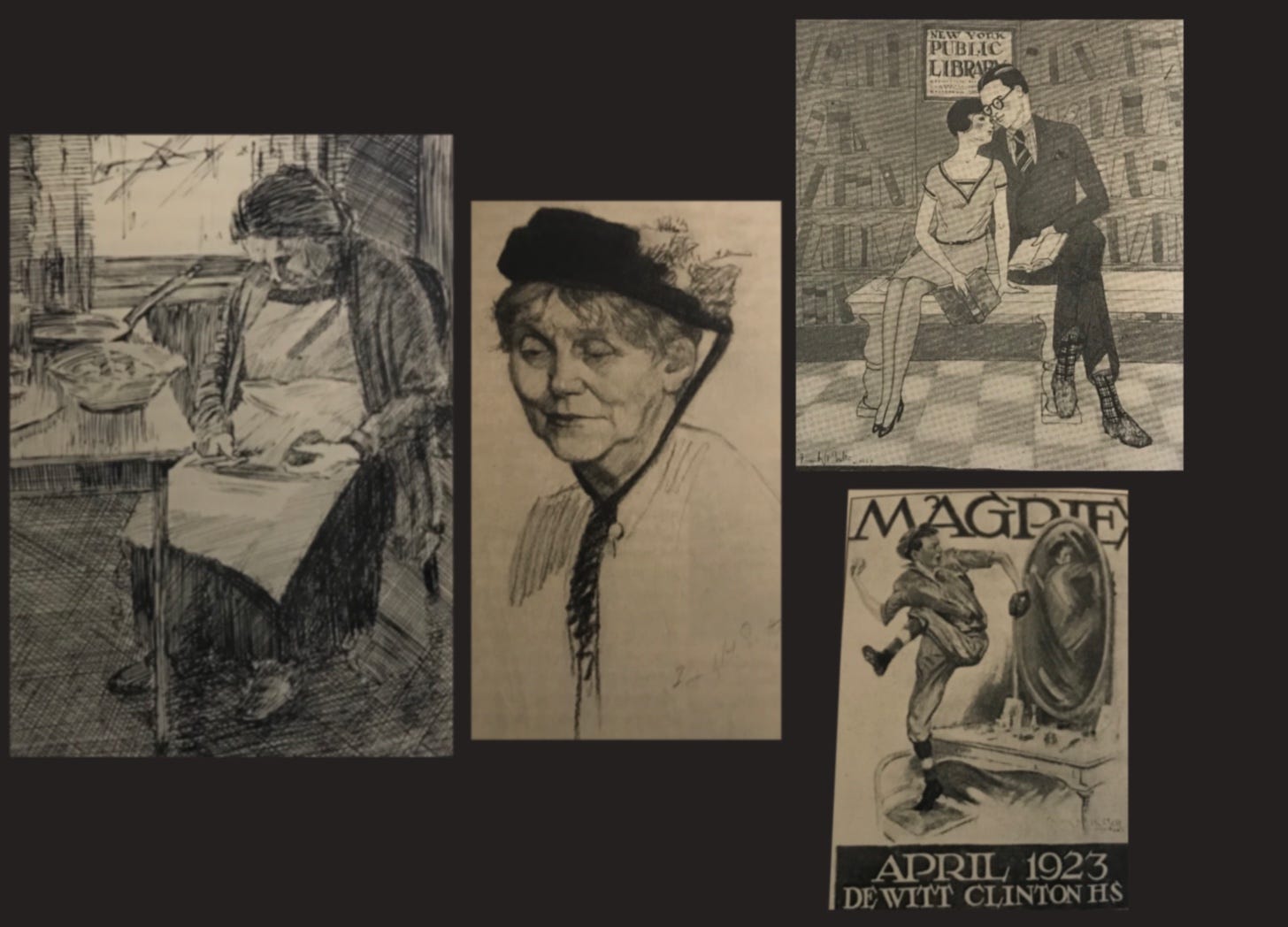

Frank H. Netter was born in NYC, the third child of Charles and Esther Netter. He was named after Ben Franklin and Patrick Henry. His ancestors came from the Alsatian region of France. Netter’s parents owned a stationery store. Netter spent a lot of time there selling newspapers. He liked to copy comics. At that time, Norman Rockwell's illustrations were popular, and Netter decided that he wanted to draw pictures for magazines. His father introduced him to a teacher who drew cartoons, pigs, and elephants. But Netter told him that he wanted to draw people. By 11, he knew he wanted to be an artist. Unfortunately, his father died of pancreatic cancer when Netter was 13, so his mother had to close the store. She wanted him to have a respectable career, so she discouraged art.

Netter went to public school and drew pictures for the school’s magazine. While in high school, he was admitted to the National Academy of Design. During the day, he went to school but secretly went to art class at night. Eventually, his mother found out, but she let him continue.

The school taught Netter a lot about art. One exercise involved a model who would come in for 10 minutes. Students had to study the figure, not draw it. After the model left, students had to draw from memory. Another exercise involved drawing the model as if looking from the other side of the room. The school encouraged students to interpret, not copy, and trained visual memory. One day, his mother came to school and asked to speak to Netter’s teacher. She asked him if Netter had any talent. The teacher said that Netter was good, but he could not predict if he would sell art.

Early adulthood, medical school, and personal life

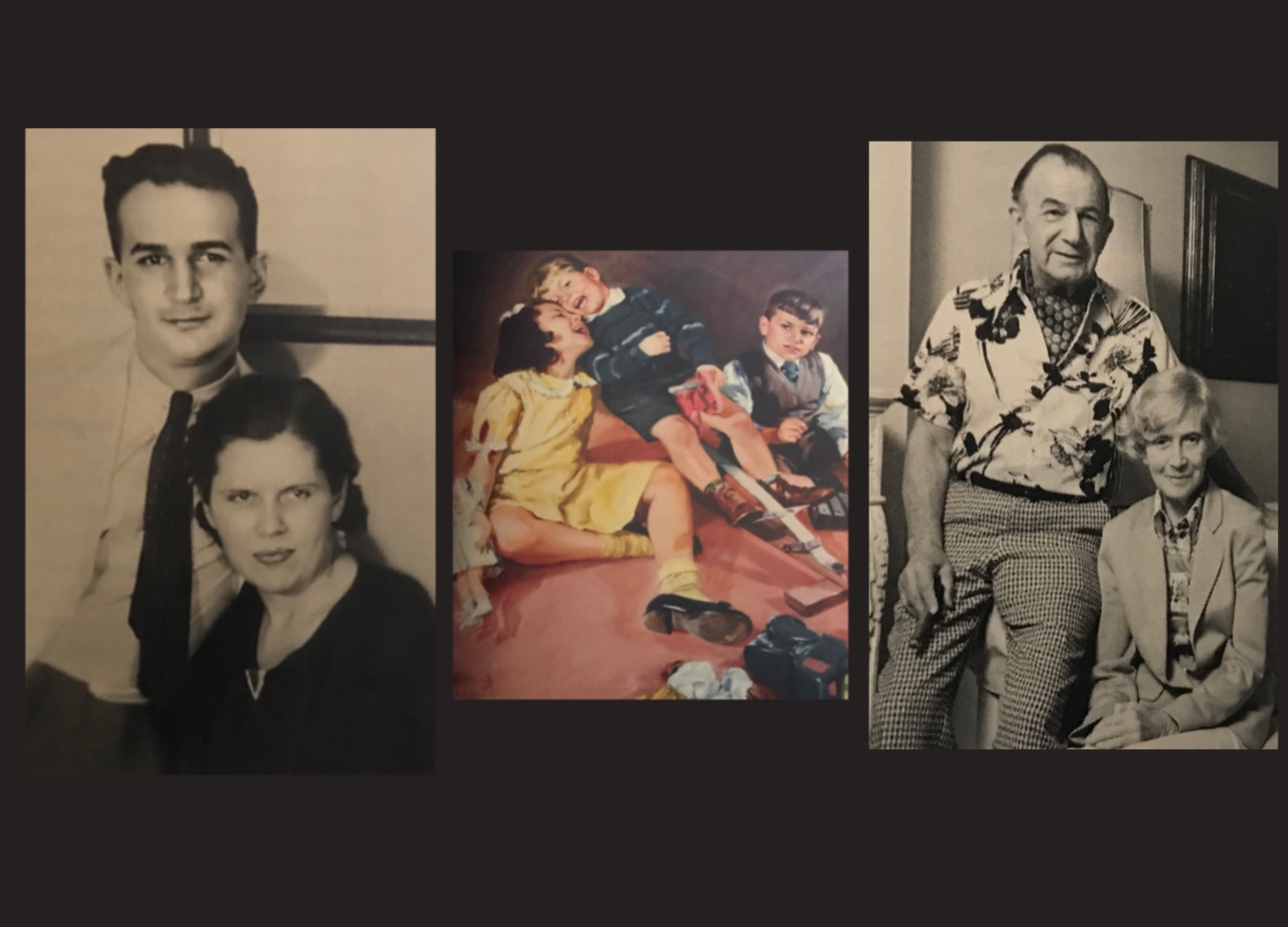

He attended CCY (City College of NY) and drew for the college publication. He was mainly a B student but received all As in his art classes. When he was 18, his mother (age 52) died of sepsis after a hysterectomy (before antibiotics). He remembered his promise to his mother, so he reluctantly decided to attend medical school at NYU. He took anatomy notes with colored pencils; he felt that he learned a subject by making pictures. His classmates and his professor frequently asked him to use them. He married a fellow classmate, Mary MacFadyen. She was known for being funny. She never wore makeup, read voraciously, and is often depicted in his early drawings. She eventually worked in the NYC Dept of Health but later gave up medicine to pursue an antique and furniture business. Netter frequently included his family as models in his work. Netter eventually divorced Mary and later married Vera Burrows, an assistant.

Early Medical Illustration

Netter was commissioned for illustrations throughout his training. At the time, doctors were paid very little. Usually, the older, established surgeons made most of the money. One day, a friend visited his office and saw paintbrushes instead of patients. Netter felt guilty. He thought that perhaps he should see patients instead of drawing. He decided to charge an exorbitant amount for his next commission to force himself to see more patients. He usually charged clients $50 per picture. For his next commission, he charged $1500. When the client agreed, he realized that making pictures was more profitable than seeing patients. So, after just 1 year of being a doctor, he resigned from his job and decided to devote himself to making pictures.

Netter was a prolific artist, making over 4,000 illustrations throughout his lifetime. He was involved with so many projects during his lifetime. The following section will highlight three of his major projects.

Major projects

Ciba Pharmaceuticals and Clinical Symposia

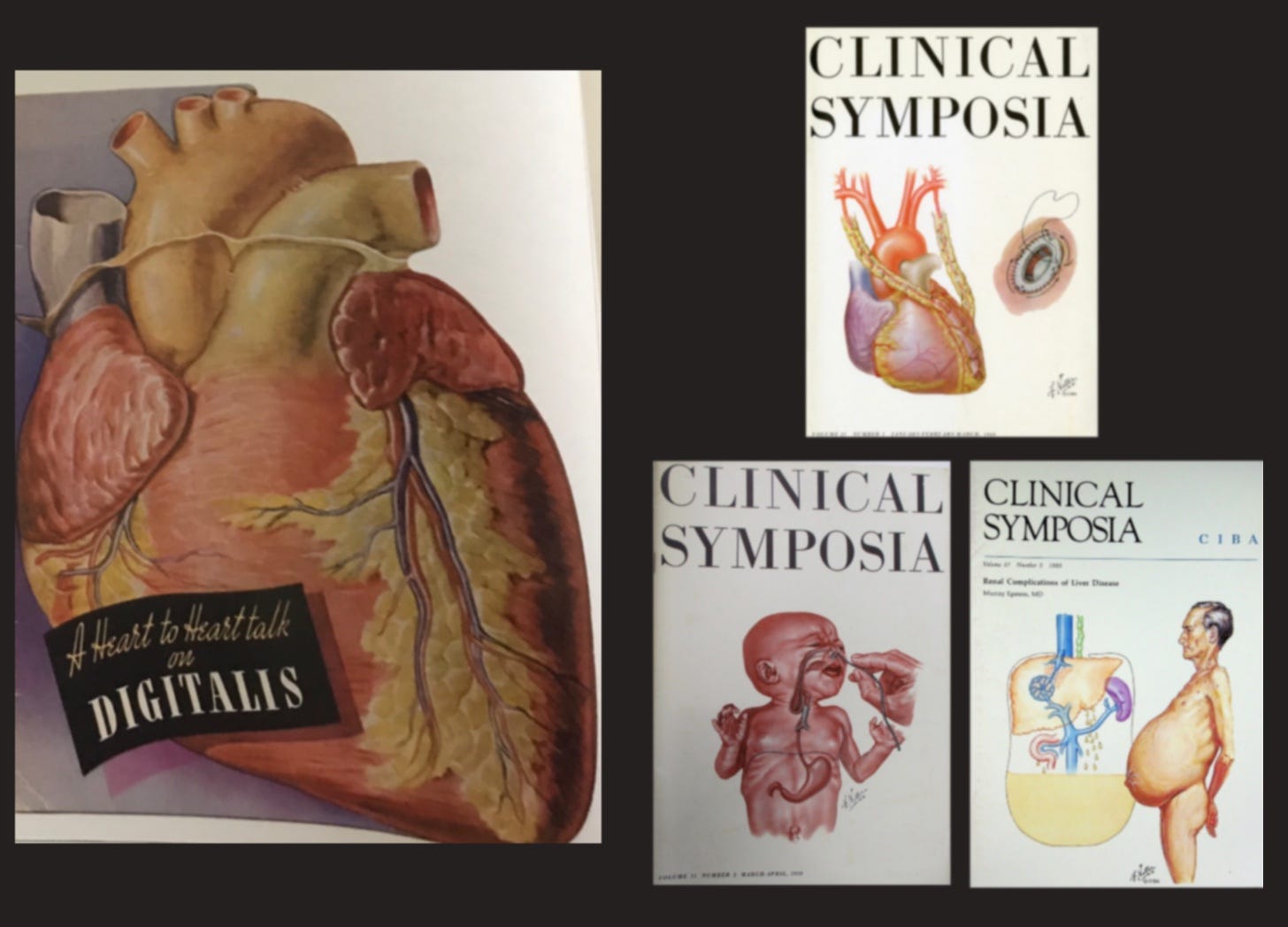

For much of his life (over 50 years), Netter worked for Ciba Pharmaceutics. In the beginning, they commissioned him to produce a series of illustrations to sell the drug, digitalis. His image of the human heart was so eye-catching, it generated so much interest among physicians. Ciba saw how powerful his images were for the medical community. They felt that Netter made them look like a caring company so hired him exclusively. Netter spent the majority of his life making illustrations for its ‘Clinical Symposia’ magazines. He consulted subject matter experts and created illustrations on various topics. He eventually produced the 12 Volume Ciba Collection of Medical Illustrations: A Compilation of Pathological and Anatomic Paintings. Many of these works served as the basis for his Atlas, which was not made until the end of his life.

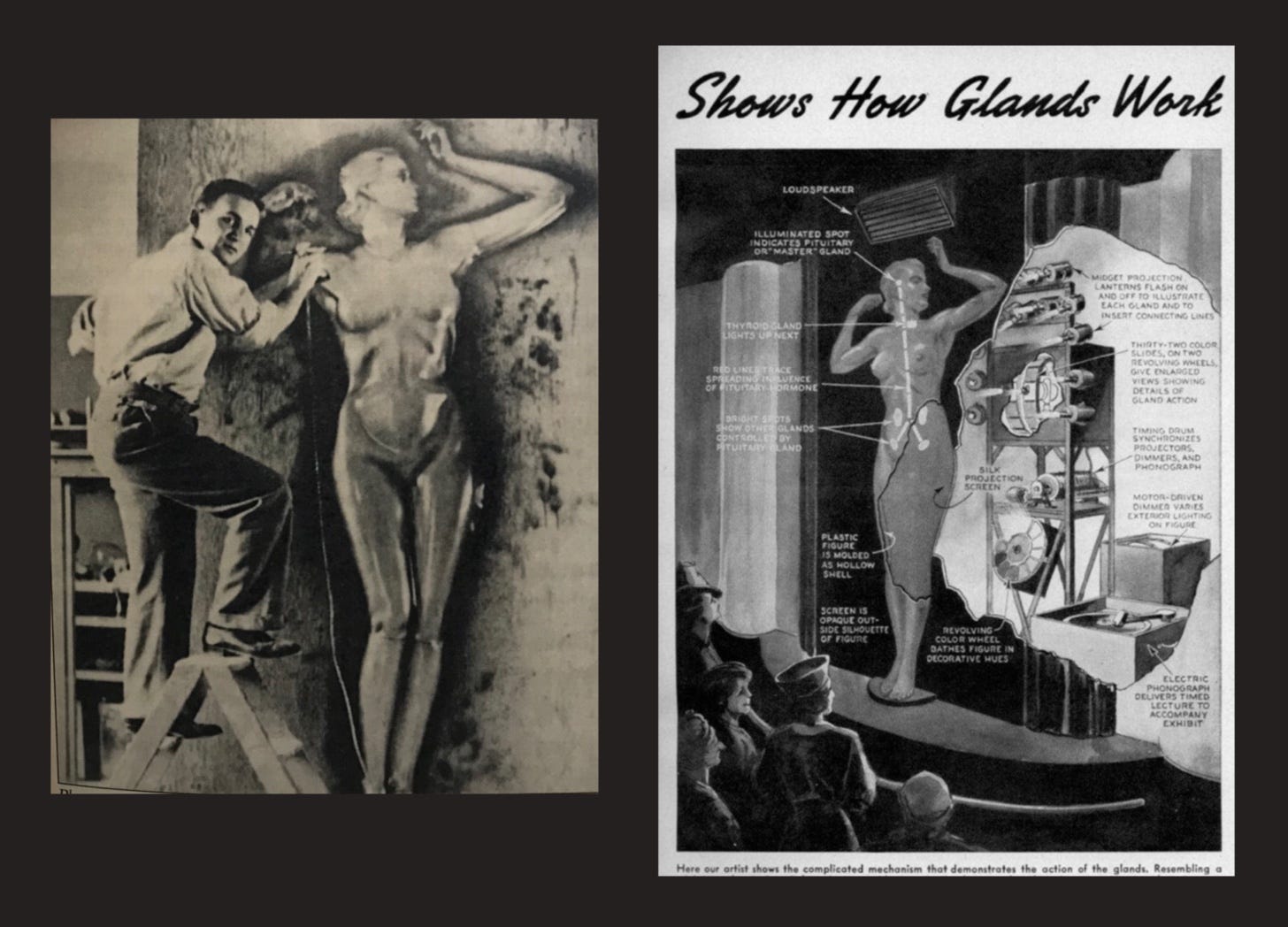

Transparent woman

Netter was asked to work on an exhibit for the exposition at the Golden Gate International Exposition in 1939. He presented Transparent Woman,’ a 3D sculpture that showed, in successive illustrations, what happens inside a woman’s body (from how hormones work to what happens during pregnancy). The exhibit, lasting just 15 minutes, used a woman’s voice to tell the story of what was happening inside her body. It was quite innovative at the time and was greeted with rave reviews.

Army Manuals during World War II

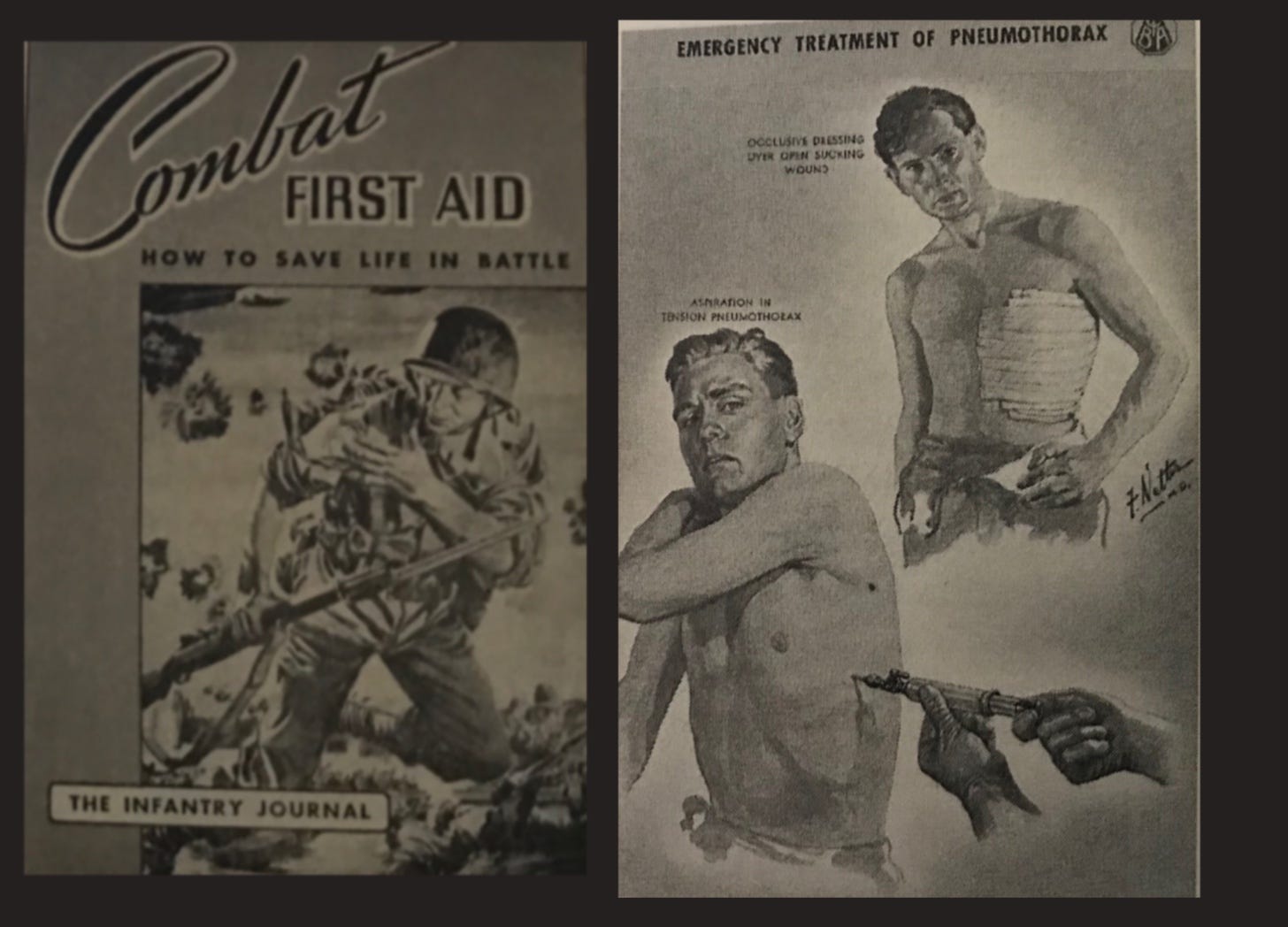

During WWII, Netter drew manuals that showed troops overseas how to save lives in battle. His images showed how to take xrays, administer first aid and perform procedures.

Netter also used his art to educate the public. At that time, charlatans were trying to peddle diet advice to the public. Netter decided to self-published a book called ‘Fad Diets Can Be Deadly.’ It was written for laypeople. He changed the wording. For example, instead of using pancreatic lipase, he used pancreatic juices. He also tried to simplify his illustrations for the layperson. It is unknown how many books he sold.

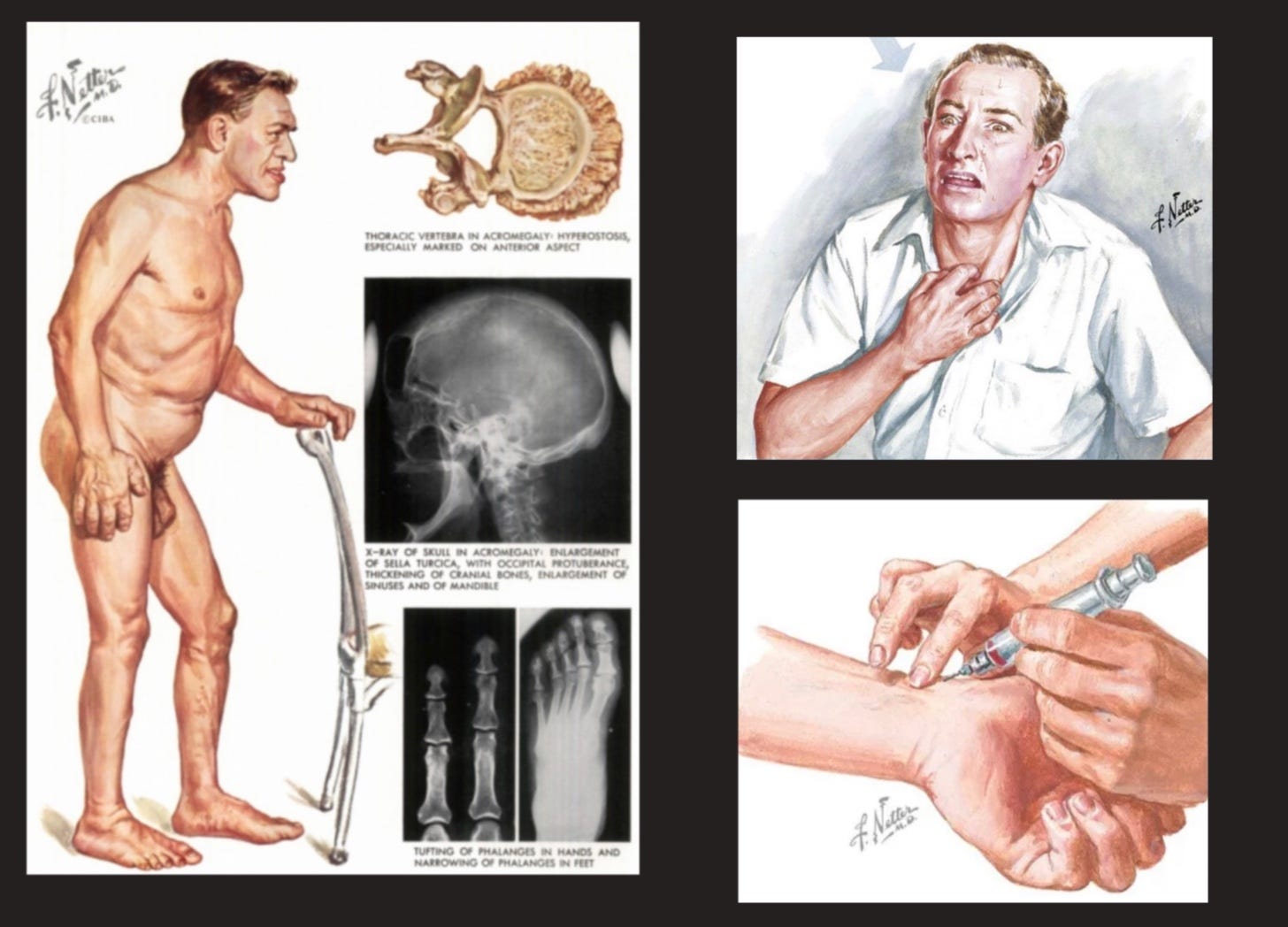

Netter was also very interested in new developments. He was captivated by acupuncture and various Eastern medicine techniques after visiting China. He was enthralled by new innovations like the artificial heart.

Netter’s Process

Netter spent a lot of time planning each picture. He would speak to experts in the field to get the latest, most accurate descriptions of what he had to illustrate. He would let a picture sit around in his head. He would spend a lot of time sketching. He would take photo references of junior staff, who often showed up in his illustrations. In the operating room, he rarely brought a camera or sketchpad with him. Instead, he observed and learned and later sketched out the anatomy. After he finalized his sketches, he would transfer his images to illustration boards. He said that the painting part was much faster. Netter preferred gauche and used Winsor and Newton Series 7 sable brushes.

He worked from 7 AM-12 everyday. At lunch, we would walk to the corner to pick up the newspaper. He worked again 12-5 and then showered and shaved. He ate dinner and played with the kids and then went back to draw.

He felt that the making of pictures was a stern discipline. He felt that writers could write around a subject when they were not quite sure of the details. But with illustration, the artist must be precise and realistic. He said, “The white paper before the artist demands the truth, and it will not tolerate blank areas or gaps in continuity.”

Netter was 5’10” and fit. He dressed in colorful clothing, favoring plaid and polka dots. He drank hard liquor: a martini for lunch, scotch for dinner, never wine. He tried to give up smoking his cigar many times, but never could. He had an active social life, going out during the evenings. Consultants would often fly and visit him in Florida, where he lived. They were not paid; it was just an honor to be selected to work with him. He was described as personable, easy to talk to, full of imagination, and not pretentious. He was unique in his ability to simplify a subject and explain it. He was very humble and would often ask for corrections. But there were usually very few problems with his work.

Netter often asked how the patient behaved. He depicted the Heimlich maneuver with a patient running to the bathroom, as this is how the patient often behaved when choking. He depicted the patient with carpal tunnel waking up at night. He learned that in certain liver diseases, there is an overwhelming thirst. He depicted the patient drinking from the toilet when the faucet had been turned off by the concerned family members.

Later Life

Later in his life, he found a tumor in groin which ended up being lymphoma. He asked his surgeons to keep the tumor so that he could draw it after surgery. While getting radiation therapy, he would spend hours in the hospital study centers, surrounded by open books, shattered sketches, and looking through microscopes and scribbling for hours. Later, Netter was found to have an aortic aneurysm that Dr. DeBakey operated on. He later died in 1991, at age 85 of congestive heart failure.

Conclusion

Netter once said that the most difficult part of illustration was keeping up with medical progress. He said that the most stimulating part was meeting doctors at the forefront—the experts. Towards the end of his career, his illustrations were compiled into the comprehensive Atlas of Human Anatomy.

Ciba Pharmaceuticals was eventually bought by Novartis and then Netter’s illustrations were bought by Elsiever. In 2010, Quinnipiac Medical School was established as The Frank H. Netter M.D. School of Medicine in North Haven, Connecticut.